Teaching Conversational NLP Systems to Ask Informative and Specific Questions

“Why is the sky blue?”

Asking questions is an essential part of our process to learn about the world from those with more experience roaming the earth, like our parents, mentors, senior colleagues, etc. Asking the right questions in a conversation could mean the difference between a focused, in-depth, and meaningful exchange of information and an inefficient, shallow, and pointless discussion.

How do we ask questions in a conversation to gather information effectively on a topic that we have limited knowledge? More importantly, can we train computers to learn knowledge from conversations?

Let us begin by understanding the desiderata for good questions to gather information in a human conversation. Among other qualities, good questions typically need to be both informative and specific.

Informativeness is an essential quality for questions to reveal information that is unknown to us from the dialogue thus far. For example, consider learning about falafels in a conversation, while only knowing that they are a kind of food. An informative question would be, for example, “What are falafels typically made from?” (the answer is “chickpeas and fava beans”1). After this question has been answered, an informative follow-up question might be “How are they usually cooked?”, which potentially reveals new information about falafels. In contrast, a question like “Do they sometimes contain fava beans?” would not be very informative since it has essentially been answered already.

Good questions are often specific to the topic under discussion as the conversation progresses besides being informative, which makes them more natural. For instance, informative questions can sometimes be very generic (e.g., “What is interesting about falafels?”), which are usually more difficult to answer (compared to, e.g., “Where do falafels originate from?”). On the other hand, sharp shifts in topic like “Where do fava beans originate from?” are also less than ideal.

| Question | Answer | Informative? | Specific? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do they sometimes contain fava beans? | Yes | No | Yes |

| Does hummus contain ingredients other than chickpeas? | Yes, they are made from cooked, mashed chickpeas blended with tahini, lemon juice, and garlic.2 | Yes | No (off-topic) |

| What is interesting about the origin of fava beans? | They are of uncertain origin.3 | Yes | Somewhat (too generic) |

| How are they cooked? | They are deep-fried. | Yes | Yes |

Can we train computers to ask informative and specific questions, so that they can learn about arbitrary topics by conversing with a human in an engaging dialogue?

The natural language processing (NLP) research community has long sought to teach computer systems to ask questions. One line of successful research efforts is concerned with asking questions about given material that contains the answer, where questions are intended to examine the answerer’s understanding of the material (also known as “reading comprehension”). Roughly speaking, the goal is to typically transform statements into a question, e.g., from “Falafel is a deep-fried ball or patty made from ground chickpeas, fava beans, or both.” to “What are falafels made from?”. However, such approaches are not applicable when the answer is not already available to the asker in some form.

Another prominent direction of research involves defining the template of information necessary to achieve an end goal, to ask the right questions about what is not already known to the asker (known as “goal-oriented dialogue”). Examples in this direction include ordering takeout from a restaurant or booking flight tickets for travel, where the typical set of information necessary to achieve the goal (the successful ordering or booking) can be well-defined. While this allows computer systems to inquire facts, the need to define these information templates is non-trivial, if not impossible, for many applications (e.g., troubleshooting a complex system).

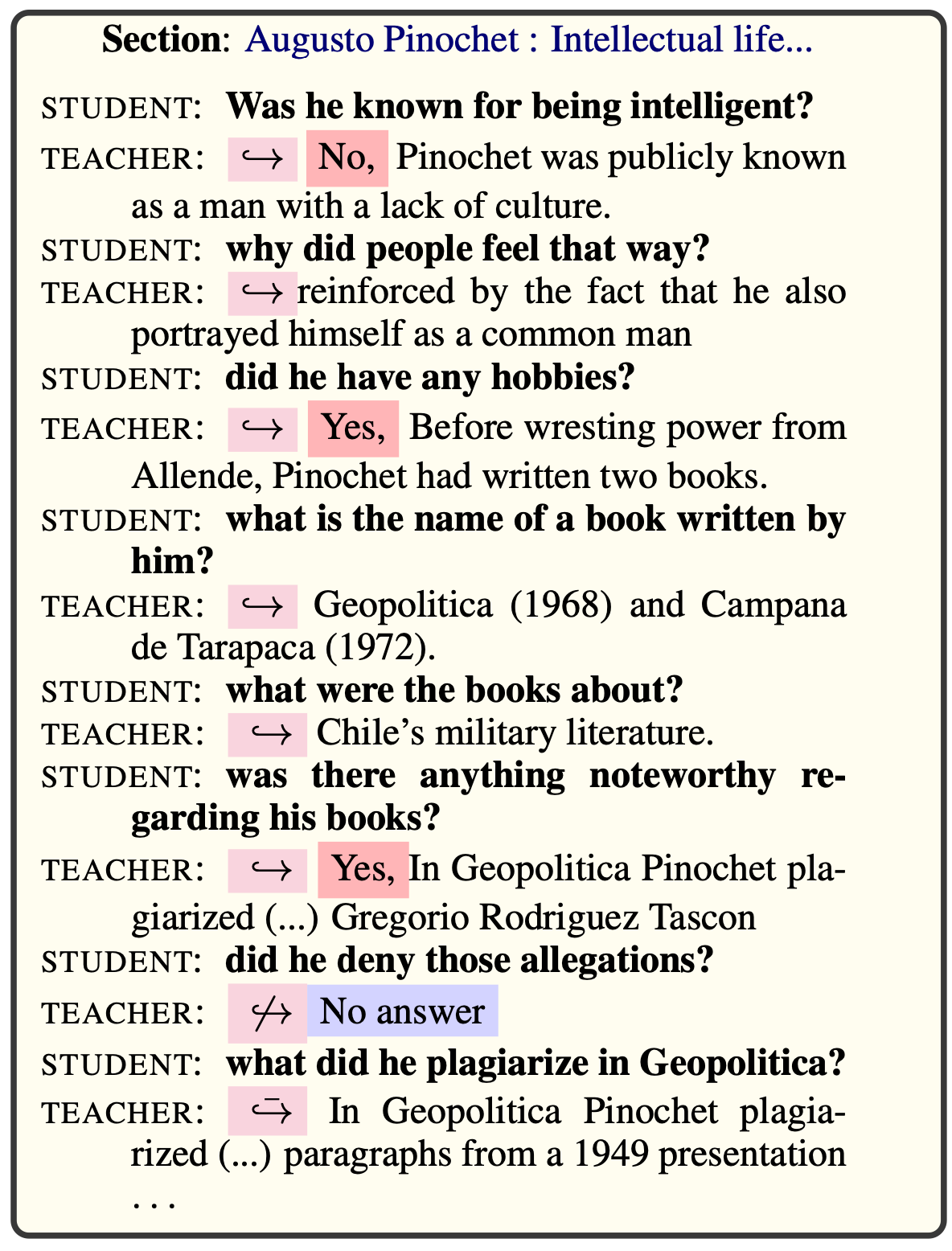

In our new work, “Stay Hungry, Stay Focused: Generating Informative and Specific Questions in Information-Seeking Conversations,” we set out to tackle this challenge from a brand new angle. We study a challenging new setting for question-asking computer systems: open-domain curiosity-driven dialogues. Specifically, we consider conversations between two agents (each a human or a computer), one a curious student, the other a knowledgeable teacher. Given a shared topic the student has limited knowledge of (e.g., falafels), the common goal of these agents is to help the student learn as much about the topic as possible by asking questions about it.

This setting has some unique challenges that make it interesting:

- The correspondence between the input and output is very weak. Specifically, the input (the conversation history and the shared topic) often bears very little resemblance to the desired output (the question), because, by definition, our goal is to gather new information that is not yet known. In contrast, NLP applications that have seen more success in recent years typically enjoy a much stronger input-output association (e.g., machine translation, text summarization, and generating questions from answer statements).

- The knowledge desired cannot be easily categorized exhaustively. Compared to more closed-domain goal-driven conversations, the open-domain nature of our setting makes it much more difficult to rely on tabulating a few things to inquire about given each topic. As a result, the student must reason about what the teacher could potentially answer on the shared topic.

- There is typically more than one right question to ask, but the data cannot exhaust all valid options. At any point in a curiosity-driven dialogue, there are usually many angles to ask questions that would reveal previously unknown information to the student. However, since dialogue datasets are collected with bounded human effort, it is impractical, if not impossible, to provide all potential questions that could have been asked naturally at any point in a conversation.

This poses challenges in two directions: the lack of diverse signal to train the question-asking system, and the lack of a good evaluation metric. While most prior work on natural language generation work can get away with evaluating the similarity between the generated output (the question, in our case) and the reference (the original question in the dataset asked by a human), questions that have virtually zero overlap can both be valid in our case (e.g., “How are they cooked?” vs “Are they typically served with other food?”, as follow-up questions to “What are falafels made from?”).

In our work, we propose two new evaluation metrics to evaluate the informativeness and specificity of generated questions. In a nutshell, we consider a question more informative if its answer contains more information that has not been mentioned in other answers in the conversation so far, and more specific if it inquires about facts that are more unique to the topic under discussion and is raised in a coherent context.

Take these follow-up questions to “What are falafels made from?” (with its answer “chickpeas and fava beans”) as an example, we can intuitively evaluate how informative and specific they are:

The QuAC dataset we use for this work contains human-human conversations on Wikipedia articles in an information-asymmetric setting similar to ours, but it provides little more than what human annotators asked and answered in each conversation. To provide our question-asking system (the student) the informativeness and specificity feedback similar to those in the table above, we proposed to train two auxiliary models on the QuAC data to derive further supervision signal.

For informativeness, since we are interested in knowing how much new information is revealed from the answer to each potential question, we took advantage of off-the-shelf question answering (QA) systems on this task. Specifically, we trained a system to predict answers given a question and the conversation history, which predicts answers from the teacher’s private source of knowledge that is not revealed to the student (usually a Wikipedia paragraph). During training time, we use this QA system to predict answers to potential questions that the student might ask, and define informativeness to be the amount of new words this answer contains when compared to the answer with the highest textual overlap among all answers that the teacher previously provided. This discourages the student model from asking questions that would result in repeated information.

For specificity, instead of relying on simple cues like word overlap, we take the approach of training a classifier to discern specific and non-specific follow-up questions, similar to the discriminator in the generative adversarial networks (GAN) literature. Specifically, for each turn in the conversation where the student asks a question, we randomly sample frequent questions from other conversations in the dataset, as well as past or future questions in the same conversation (which we consider specific), and train a classifier to distinguish the actual follow-up question from the rest with high accuracy. Once this classifier is trained, we use the probability it predicts a potential question as specific as the question’s specificity score. This discourages the model from jarring topic shifts or even digressing off-topic.

To train our question-asking model (a sequence-to-sequence model) to generate questions that are both informative and specific, we first train it to maximize the probability of generating the reference questions in the QuAC dataset, then finetune the model with reinforcement learning to maximize our informativeness and specificity scores.

The result? Our finetuned models fare better when evaluated by our informativeness and specificity metrics, while standard metrics like perplexity and ROUGE, which are commonly used in natural language generation evaluation, fail to tell these systems apart.

To give you a more concrete idea of how these systems behave, here is an example where we list the original reference, the question from the baseline (non-finetuned) system, and our system after incorporating informativeness and specificity, see for yourself which candidate questions you prefer (try to evaluate the questions before you read the answer, as the answer is only compatible with the reference question):

| Background: Spandau Ballet (English band) Topic: 1983–1989: International success and decline Candidate Questions |

|---|

| Question 1 |

| Candidate 1.1: What happened in 1983? |

| Candidate 1.2: What happened in 1983? |

| Candidate 1.3: What was the first indication of Spandau Ballet’s success at the international level? |

| Answer 1 The follow-up album, Parade, was released in June 1984, and its singles were again big successes in the charts in Europe, Oceania and Canada. |

| Question 2 |

| Candidate 2.1: What was the most popular single from the album? |

| Candidate 2.2: What were the notable songs from the album Parade? |

| Candidate 2.3: What was the name of the album? |

| Answer 2 The album’s opening song, “Only When You Leave”. |

| Question 3 |

| Candidate 3.1: How did the opening song do on the charts? |

| Candidate 3.2: What other songs were on the album? |

| Candidate 3.3: What was the name of the album that was released? |

| Answer 3 Became the band’s last American hit. |

| Question 4 |

| Candidate 4.1: Are there any other interesting aspects about this article? |

| Candidate 4.2: What was the last album that they released? |

| Candidate 4.3: What other songs were on the album? |

We hope you agree with us that candidates 1.1, 2.3, 3.3, and 4.2 are usually of the poorest quality in their respective group, which is generated by the baseline system without finetuning for informativeness and specificity. Our system is much better at inquiring about new information while staying on topic (1.2, 2.1, 3.2, and 4.3), arguably even more specific than the human reference (1.3, 2.2, 3.1, and 4.1) at times.

To confirm our findings, we also conducted a larger-scale human evaluation, and after examing 200 groups of predicted questions in a blinded experiment, our annotators agreed that our system generates informative and specific questions more often than the baseline system, and the with higher overall quality. All human evaluation results are validated with statistical testing, which demonstrates statistically significant different differences between these systems on these metrics.

We hope our work can help highlight the importance and challenges in building natural language systems to gather knowledge through a natural language interface, and more importantly, a practical means to train these systems to reason about the unknown in the face of information asymmetry. If you are interested, please check out our paper for more technical details, analysis, and bibliographical notes. We have also released our code and models, should you be interested in training and running these models for yourself!

Footnotes

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: