What do industry researchers do, anyway? Part 0 -- Academia vs Industry

You are embarking on a grand journey called pursuing a doctorate, have been immersed in it for a couple of years, or are almost Ph-Done and cannot wait to pursue your dreams after the program.

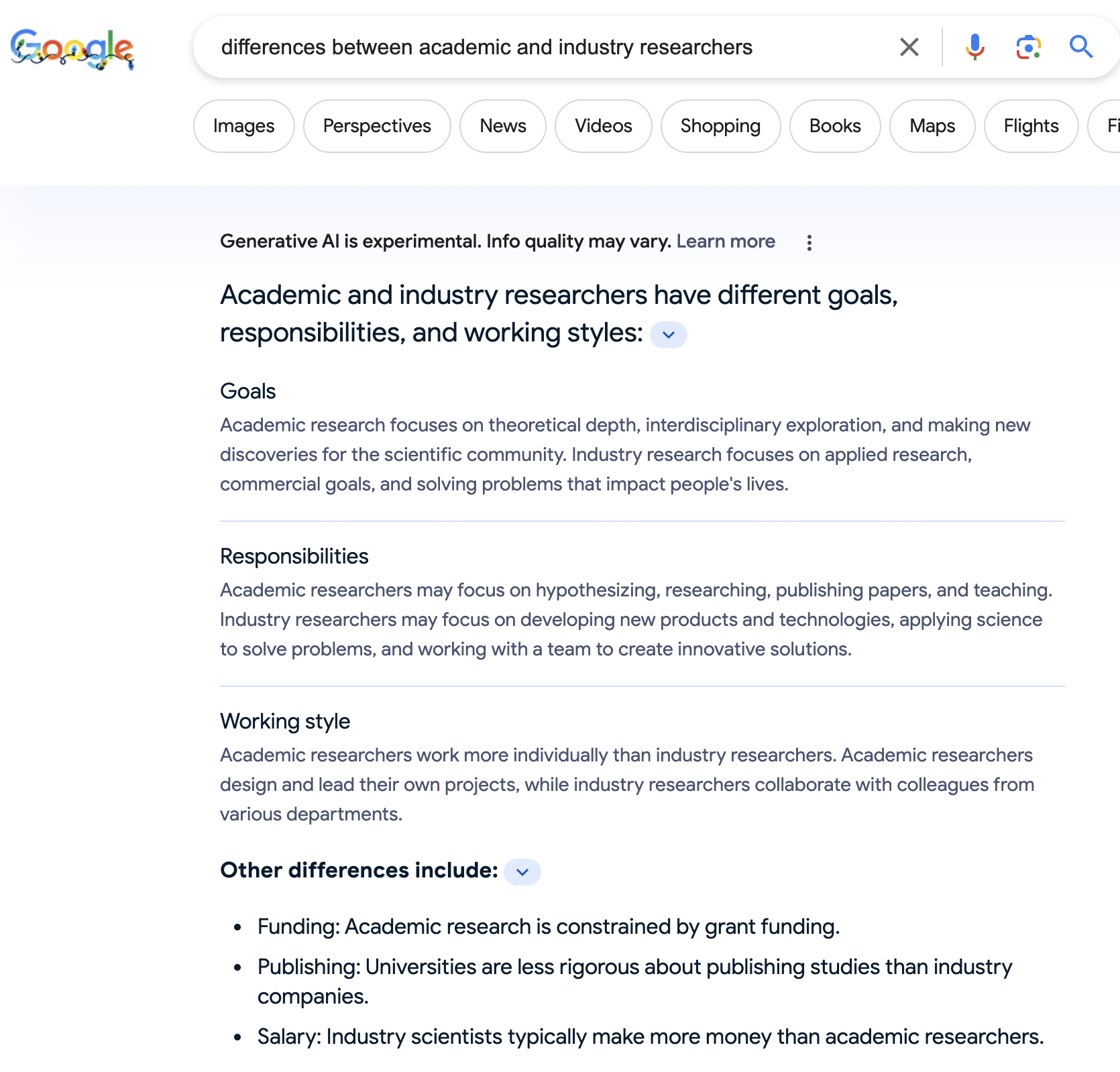

Many would imagine themselves on the path that brought them into the doctorate program in the first place – continuing to pursue a research career in academia or the industry. You have a general notion of what they might entail to a first order of approximation (in fact, Google did a pretty good job summarizing it, see below). But in the back of your mind, you cannot help wondering, would the grass be on the other side?

In this post, I hope to record some of my observations along the way to help highlight some factors of consideration I would have shared with my younger self.

Why might you want to continue/stop reading

Before sinking more valuable minutes into this post, you might want to ask, who is this for, and why should I trust the author’s experience to be relevant to my own? Both of these would be very relevant questions.

A bit about myself at the time of writing: I have been an industry researcher for a little over 3.5 years. My time has been split between two companies and two very different roles, one where the primary goal was to publish academic research, the other more on the applied side with a focus on putting great technology into products. Before these “real jobs”, I finished a PhD in Computer Science at Stanford, did a research-focused Masters before that, and did some undergraduate research when people around me are still not sure what to make of “cloud computing” and “deep learning” (are they simply just larger compute clusters and deeper versions of the same neural networks that nobody teaches in undergrad courses any more since they didn’t work? Spoiler: the answers are no and no).

In these experiences, I was fortunate to have worked with a good number of amazing research mentors and peers on very different research topics and problems, published a few papers, some of which – fortunate of me – you might have even heard about. I have worked on and witnessed many research projects that never saw the light of day, and seen my fair share of faculty interviews both as a student interviewer and a faculty interviewee. On the other hand, I have also seen how research is done in industry labs as a research intern, a many-a-time intern mentor, a researcher as part of a small research team that published on diverse topics, and a “founding” applied scientist on a more product-focused team that helped launch a brand new product (almost) from scratch, while publishing some fun papers along the way.

Now that’s out of the way, let’s get on with what this post is about.

The less talked-about similarities between academic and industry research

Before covering some of the differences between industry and academic career paths, I wanted to first reflect on what feels quite similar between the two.

Both academic jobs and industry jobs are just that, jobs. Freshly minted PhDs are usually equally surprised by the job-like natures of these, which typically comes with more responsibility and very real-world “consequences”. I think this stems from two common factors.

The first one is that you don’t work alone any more. Gone are the days that only you depended on your PhD thesis and research progress yourself, where you can spend hours and hours noodling over the same problem, and if you miss a paper deadline, there seems to always be other ones right after. In both academic and industry jobs, you work with a number of other people towards a shared goal, and they would sometimes depend on you for resources, output, time commitments, or all of the above. This means you spend a lot more energy on making predictions of your own output, as well as making sure you make progress as predicted or communicate early on otherwise. This also means you potentially spend a lot more time and energy on your responsibilities to budget, plan, and allocate resources (time, $$$, people) to make sure things go roughly as planned.

The second factor is simple economics, where if something has high unit cost, you get nothing produced by splitting that investment n ways. Since most meaningful research projects are resource intensive, society/private companies simply cannot fund everything that comes to everyone’s mind. As a result, we usually gravitate to simple heuristics that “past performance predicts future success”, and use people’s track record to establish our trust in them and support their research endeavors accordingly. This imperfect heuristic sometimes makes successes and failures in research jobs feel more consequential than the handful of papers you publish as a PhD student, since you are no longer shielded behind the great buffer that was your advisor for resources to do your research – you’re a little more on your own (though great communities exist in both jobs to soften this).

A third common factor that might not be obvious to fresh PhDs is that regardless of whether you go to academia or industry, the chances you work with domain experts in your day-to-day likely diminishes. This could be viewed as a corollary of not working alone any more, because as you work with more people, you are also typically exposed to people with different background. You get a glimpse of this during your job talk, where even the really smart faculty members of a department you are visiting probably didn’t fully understand everything you said, or that the senior researcher from a neighboring group is fascinated by some mundane details to insiders that isn’t even your contribution. But there is always more. Great collaborations during your PhD is often cherished, because it’s rare to have someone understand a topic as deeply as you do and together make exciting contributions that inspire all of you, and because “you will eventually write different theses” so it won’t last forever. This is a bit more pronounced for academics, but both academic and industry jobs entail a lot more interactions with non-experts (your university admins, senior colleagues, grant reviewers, engineers, product managers, etc.). In both of these cases, the ability to communicate with someone outside of your comfort of scientific language and jargons becomes really important to get the point across, to manage expectations, and to meet them where they are – which is their professional area of expertise – to achieve your common goals.

I should note that many of the things described in this section sound like managerial duties, because they are. These are typically a lot more pronounced for junior faculty compared to industry researchers right after their PhD, since industry folks typically don’t get to “run a lab/team” until much later (and many choose not/never to).

Two roads diverging in a wood: where academic and industry research jobs differ

Having covered the commonalities, I also wanted to reflect on some of the underlying factors that set the two apart.

First and foremost, academia and industry have different definitions of goals. This is not the simplified argument that “industry is profit-driven and everything contributes to that”, because that usually elicits a very skewed and cynical image for junior researchers facing this choice at the juncture (or even seasoned ones that have been in academia or the industry for a while). I’d like to think of it more as academia is pursuing original knowledge and that’s the end goal in and of itself, while industry is always trying to put things in hands of actual people in the long run. This means academia has a lot more freedom to pursue things that help us understand things better (but not necessarily do them better), that do not have practical implications for decades or generations, or that are scrappy and do not extrapolate well. Industry labs, on the other hand, are typically a lot more focused on the real-world, and sometimes even with a reduced emphasis on originality. As a result, the outcomes from research endeavors and their runways (time/resources taken to build the research projects) perceived wildly differently between the two. In fact, it is likely that you’ll see goals defined a lot more homogeneously across different academic groups compared to industry research units, where the latter can be tasked with research of different time horizons and quality expectations to produce a usable product.

Second, academia and industry often adopt different measurements of impact. Impact is a stamp of approval for the “goodness” of your work, and is often associated with good opportunities. While academia is more about “how much new research is enabled and inspired by your work” (often proxied with the problematic metric of citations), industry typically focuses more on “how many people or $$$ are affected, and how soon”, since that’s what keeps the endeavor afloat and pays the bills. As a result, academia and industry often take very different strategies to tackle similar problems. For instance, if something’s not making progress soon enough and resource is the main bottleneck, it’s often much easier for industry research labs to “ramp up resources” and throw it at the problem, while academic researchers might spend more time on optimizing the process in place. In other cases, while academic researchers might firmly stick to challenging problems for years till fruition, the industry typically waits till the first inklings of practical implications from such original research before making a substantial move. While both are by and large really good at what they do, each of these measures of impact, when taken to the extreme as the sole focus, can lead to troubling outcomes.

Last but not least, academia and industry have very different scales of operation and connection to real users. The first might be easier to understand. While most PhD students played the “full-stack engineers” or equivalents in their own research projects, there is only so much a single person can do in 8 hour workdays, and users ask for a lot more than your scrappy prototype. In an actual product, you typically work with a number of folks that are more experienced and talented at various stages of that full stack that your bandwidth and expertise can never hope to scale to. As a result, the industry has some of the most trusty products that real people use and often give feedback on, which no amount of lab surveys and simulations can replace – which is the second point. This also means that academics will never get to work with some of the “messy” yet challenging problems, both researchy and non-researchy ones that are brought about by scale, but more often just the “real-world distribution of data and problems”. Needless to say, this access is accompanied with great responsibilities, and user needs are usually more demanding than what careful research solutions take, which industry researchers often need to grapple with.

So, what does this mean for you?

If you’ve read this far, hopefully this post has provided some useful frameworks to think about your choice and helped you get a sense of what to expect. I have personally been fortunate that my research interest lies in a wide spectrum that spans from “this is an interesting idea for the idea’s sake” to “let’s make a thing that works”, which helped expose me to both paths somewhat. At the end of the day, you might ask what excites you more at the moment, what you will likely continue to enjoy the most, and make your choice accordingly. In the next post, I’ll try to cover how I think you can get the most out of selecting a team in the industry, which hopefully gives more practical suggestions on making this choice.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: